The New York Philharmonic sexual assault coverup story continues to unfold. Yesterday I found myself reading screenshots posted by oboist Katherine Needleman. I’ve never met her personally, but we’re just one degree of separation removed from each other. She is doing amazing work on Facebook on issues of misogyny in our business, and is linked in the article above.

The name of the person who wrote the messages was hidden, but his identity was obvious from their content: Alex Klein, a storied oboist who has held some of the most prominent posts in the country. He was advising a younger oboist not to support Needleman in sharing information about the NY Phil coverup, and indeed to scrub her social media of any links to Needleman’s content.

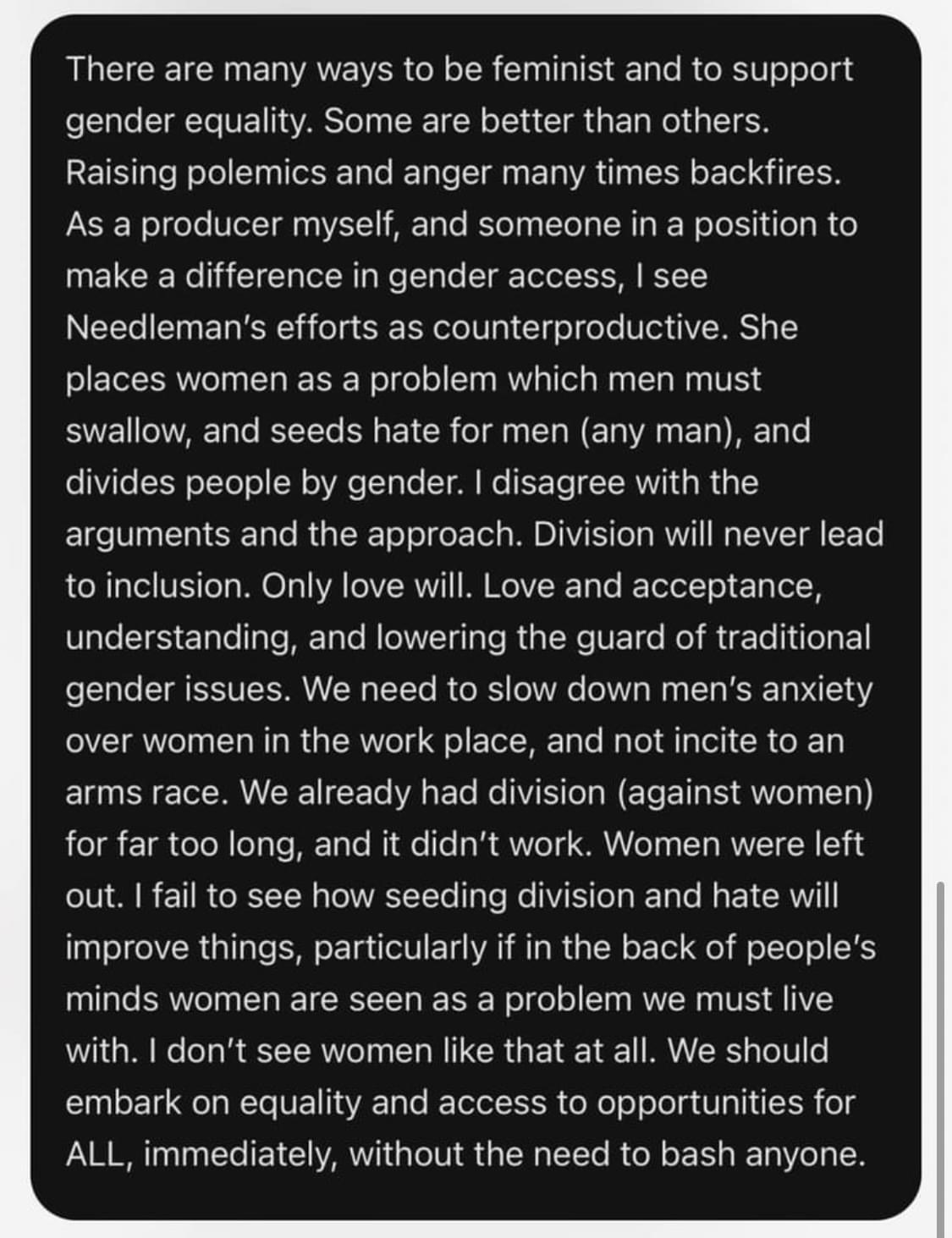

He wrote the following, presuming his younger female colleague to be someone who would not share his words, out of fear or deference or whatever keeps us all in line:

In case you haven’t read about this whole mess, you might check out the link at the beginning of this post - but go at your own pace. I sure don’t feel like recounting the awful details here after a few days soaking in them.

I did want to share Alex Klein’s pro move, however. This powerful man gives a veiled threat to a younger female colleague (as someone “in a position to make a difference in gender access”), advising her to distance herself from “anger,” which is not one of the “better” ways to be feminist. Apparently what’s needed in response to yet another instance of an institutional assault coverup (how many are we on now? are you all counting?) is “love,” and a slowing down of “men’s anxiety.” Also, we should get right on with the work of equality - immediately! OK Alex! - but no bashing. Heaven forfend.

(Alex, does bashing mean holding someone accountable? Asking for dozens and dozens of friends).

Many men all over the internet and irl are doing better than this famous yahoo, of course. But many are not. And, colleagues of all genders within the NY Phil stayed silent until their hands were forced by the latest news. This pattern has been repeated in institutions all over the country.

Why is it so hard for us to stop it?

In the meantime, as this shabby lil story began making the rounds, our students were opening Speed Dating Tonight! at Baylor. The composer and librettist, Michael Ching, describes the piece as a “new numbers opera” (traditional opera is a series of “numbers” - solos, duets, trios, and so on through larger ensembles). Ching’s been composing new material every year since SDT’s premiere in 2013. Our director, Jen Stephenson, has been calling it a “choose your own adventure” opera, and that’s a great description: there are now more than 90 pieces to choose from and combine in almost any way you wish in the process of constructing your company’s version of SDT.

The opera works with any group of singers: any number, any combination of voice types. Every artist can find something that’s right for their voice and their personality. Everyone is featured. You can see the practical application for university settings right away; no matter the makeup of the cohort, this is a show you can cast well. And that’s the way I’ve most often heard the opera described, as a practical, utilitarian work designed to help out your usual unbalanced college opera program. No big deal if you have mostly sopranos or lots of undergrads or beginner pianists, SDT’s gonna be doable. And there’s the added advantage of everyone having a solo turn, which is a great thing both pedagogically and collegially.

So, what a great thing for the students, right? But also - what a rare event in opera, for everyone onstage to experience such equity in both performance and agency. Everyone has an aria, a character, and a choice, everyone is singing something they felt drawn to and care about. There are no secondary characters, and no stars.

There are also no vocal stereotypes.

In our cast, we’ve got sopranos who can float vulnerable high notes, mezzos who can bring the chest voice, tenors who can Chris Cornell it in a classical way, and baritones who can get all angsty. All those singers can also do other things with their voices; the particular things I’ve listed, however, are basically traditional opera’s go-to vocal personas, corresponding to Victorian-era stage stereotypes (Victoria’s reign, 1837-1901, covers a very large portion of opera’s European heyday).

Sopranos tend to be ingenues, young women whose innocence, purity, and vulnerability are often expressed through pristine, controlled high singing. A soprano voice with richer, more complex colors and vibrato will be coded as more sexually knowing, and at the far end of that spectrum are the crazy ladies. Mezzos still talk about playing “witches, bitches, and britches” - they begin, as sopranos do, at the sonically leaner end of the spectrum singing boys, developing with volume and opulence into destructive women, danger expressed through their lower tones and less controlled singing. Tenor characters tend to be despairing and ardent, crying at the top of their range. Baritones tend to be angry and tortured, never getting the girl, veiling their middle range and going all out on the high notes but keeping some of that veil so that they are not misgendered as tenors.

Since opera’s always been the most potentially lucrative option in the classical vocal world, a lot of our training formed around it and continues to emphasize the requirements of the most commonly programmed works. Even singers who never dream of singing opera are probably negotiating information about what type of voice they have, and what repertoire is right or best for them. A lot of our teaching practices tend to move developing voices in the direction of one of these long-prioritized Victorian personas. Opera has had a harder time moving forward in non-traditional casting than spoken theater because the above, highly-gendered vocal expectations are baked into our compositions.

But pieces like Ching’s SDT choose a different kind of vocal dialect, one that consciously avoids the above stereotypes. It doesn’t require singers to adopt any of the traditional vocal and/or expressive postures unless they choose to - and anyone can choose to adopt any of them, the repertoire adapting to the individual rather than the other way round. Singers in such a work can use their particular gifts in whatever way they choose, or not use them at all, depending on what they each want to say in their chosen arias with their voices. That floated high note might mean vulnerability, or it might mean something else.

And then, we in the audience have the opportunity to hear them differently, should we choose to be in the moment with them, not listening backwards into a vanished past.

The vocal writing in Speed Dating Tonight stands in sharp contrast to opera’s most common vocal postures, and it’s not alone. Many new works, however, still deploy voice types in a very traditional way. It takes time to create a new language, for speakers of a common tongue to recognize that new words and structures are not necessarily simpler, messier, or beside the point, but rather are attempting to say something the current language can’t express.

Another thing that happened this weekend is that I got to listen to Sojourn, the newest release from pianist Jess Johnson. Johnson, who teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has put together a fab program of piano music by living women composers (six of the pieces are commissions). You’ll find her playing very beautiful even if you don’t know this cool fact: she’s playing on a DS Standard 5.5 keyboard. This freaking ingenious keyboard has narrower keys, appropriate for smaller hands. It can be inserted into your big old grand piano and then you can reach intervals and comfortably crunch chords that may not have been possible for you before.

This is not a niche pianist issue. Although historically keys varied in size and were generally significantly narrower, modern pianos have keys that are too wide for a majority of women and a significant number of men. I can reach a ninth on a modern keyboard if I stretch, which makes a large portion of repertoire written since the 1850s inaccessible to me. But we have one of these inserts at Baylor - I’ve tried it and I can reach an eleventh! So not only can I take on some of the stretchiest rep on this new keyboard, but I may well experience less injury and fatigue (women pianists are twice as likely to experience injury as men, and injury is extremely prevalent throughout pianists’ lives). It takes a little adaptation, but any pianist who also plays synthesizers, harpsichords, or organs (and that’s most of us) already switches between different key widths.

So why did this take so long? Especially when we consider that women have been playing the piano in large numbers right along men the whole time? And when we also consider that some pianists themselves have been adapting keyboards along to make things better for their own hands - notably the great Joseph Hoffmann?

Because it took us a long time to see what we thought, to hear our common languages. The language of progress: bigger is better, so a nine foot piano with wider keys and a more powerful action is the best. The language of achievement: you will sweat and suffer in the course of striving to become great, and if you get hurt it might just show that you’re not cut out for the career. The language of patriarchy: if the situation excludes women or makes things harder for them, does that not simply prove they are not suited? The language of exceptionalism: if we modify things so that anyone has a shot, doesn’t it diminish the achievements of the few?

Who gets to make noise? And what are our noises supposed to sound like?

In one of my early jobs, I had a single one-on-one conversation with my boss in the six years we worked together. He took me aside and proceeded to praise an absent colleague of mine, the only other young woman on the music staff. “She always smiles,” he said. “And she usually keeps her opinions to herself. So when she speaks, it really means something.” Here he looked directly at me. “Not like people who talk all the time. No one likes a know-it-all.”

Now look, I’ve met me. I do talk a lot, and I am a know-it-all. Fair. So, at heart, this was useful advice, my boss advising a young woman she’d do well in his workplace by emulating another woman whose behavior he liked better. His comparison of the two of us underscored the gender piece’s significance; there were multiple polite, circumspect men on staff who might have been held up to me as beacons of quiet, but I can’t say how my boss perceived them, and I don’t know if he ever took them aside to ask for more or less. What was clear was that I was making too much noise, and that my loud opinions would somehow have more meaning if they were almost never spoken.

If it costs us to swallow our opinions, not complain, keep the secrets, et cetera, what’s also clear is that it costs a lot to damn the torpedos and talk anyway. The professional retribution exacted for talking about the worst practices in our profession is real and significant, and many people are in circumstances that make it very, very difficult to risk it.

It’s so inspiring to watch Katherine Needleman, Lara St. John, and others using their privilege and status to takes these risks. This morning, Needleman is sharing messages sent to her by Alex Klein, screenshots of Messenger conversations between a couple of other professional men musicians who use incredibly vulgar language to describe her while discussing her coverage of the NY Phil story. Once I got over the junior-high-bathroom vibe of it all, it was easy to see the same pattern I’ve witnessed and experienced in my life. Talk about the bad thing, and someone will come to let you know - see what they say about you. No one likes you. You should be quiet, and don’t tell anyone about this. Do you want it to escalate?

More people will listen to you if you stop talking. Obviously, that’s a crazy thing to say. And to hear.

But it’s also a way of saying, hey, this is just the way the instrument is made. This is just the way the language works. We forget that we construct all of these things, the instrument, the language, the idea of how the music is supposed to sound.

We can reconstruct it too. Does that reconstruction start with the instrument? the language? or with the human heart?

We’ve made some progress with the first two. The work on the third is harder, and up to each of us individually.

I hope that the orchestras in which those vulgar messenging bros play will hold them accountable to standards of conduct.

I hope that unions will take the protection of all their members seriously, and that union members will use their voices to talk about what their dues are funding.

I hope that we are not so deferential to our legacy that we work against the inevitable, vital development and change of our languages and our technologies.

And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go practice some Rachmaninov. Because my hands are not too small to make that big music sound, if the language and tech are mine to adapt.

Your hands are also the right size. Grab hold.

Thanks for this one:

to the brave and loud Katherine Needleman.

to the power of social media to amplify noises we have collectively decided not to hear for so long.

to everybody who is doing what they dare to do in this long fight, even if that feels like not very much. A little change is astronomically more than no change. Keep the faith!

And if you want to read more about pianos and the equitable, anti-sexist and anti-racist implications of modified piano keyboards, check out this incredible resource page from pianist Rhonda Boyle, founder of PASK (Pianists for Alternative Sized Keyboards)!